This post was written by Fabian Tompsett, Wikimedian and co-ordinator of the Wikimania support team, and originally published here.

I am just coming to the end of a four-month stint working for Wikimedia UK helping to deliver Wikimania 2014 at London’s Barbican Centre. It was all quite exciting and as The Signpost put it was “not too bad, actually”. In the whirl of events seeing dozens of hackers bringing hacking home to Hackney, hunched over their laptops, while other devotees were busy tweeting, it became all too easy to miss some key aspects of the event, and so to fail to recognise that Wikimania contributed to saving lives.

Wikipedia is not just a website, it is also a somewhat heterogeneous international community which thrives on face-to-face encounters in meatspace. For myself my involvement gained an extra dimension when I started attending the regular London Meetups six years ago. It was meeting other human beings rather than tapping away while staring at a computer screen which made it interesting.

So, this August the London Meetup page modestly subsumes Wikimania within its calendar of monthly events, within an expansion to a three day event with between 2,000 and 4,000 attendees (so much for “British understatement“). But in essence it is the face-to-face interactions outside the formal sessions which make Wikimania such a powerful event. I don’t want to be dismissive about the formal sessions and all the hard work which went into them, it is just that I want to focus on the other aspects and use this to show why I believe Wikimania saves lives.

A couple of weeks after Wikimania a discussion opened up on the Wikimedia Ghana list which spoke of an initiative by Carl Fredrik Sjöland of the Wikipedia:WikiProject Medicine who have teamed up with Translators Without Borders to set up a Translation taskforce. As they explained a couple of years ago “We believe that all people deserve high quality healthcare content in their own language.” Faced with the current Ebola outbreak in West Africa the focus of these activities has shifted to finding people to translate information about Ebola into the relevant indigenous languages. There is something similar happening through the Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team who have also been very active developing mapping resources for the medics on the ground.

I had hoped to make it to the OpenStreetMap 10th Birthday Party (the London celebrations were held nearby, to coincide with Wikimania) but I got caught up in other things and only arrived after most of the people had left. But that was precisely what Wikimania was like: you find out more and more about it in the aftermath.

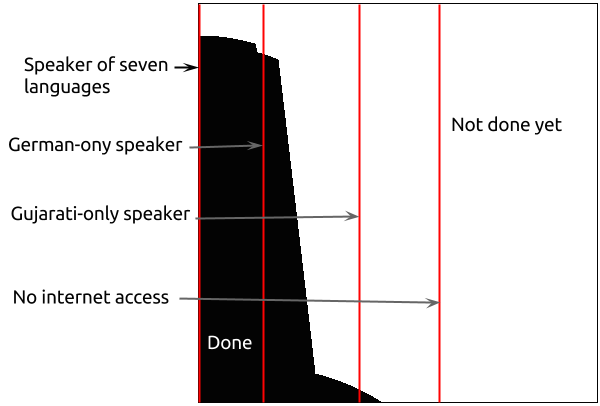

Another aspect I found out afterwards was Denny’s comments on A new metric for Wikimedia where he discusses the availability of Wikipedia in different languages. Considering the recent Ebola outbreak above, this is not just a “nice idea”, but something which requires support now. Often it is not so much getting hold of finances, but finding a way in which those people with the relevant language skills can be linked up with and given the resources to make things happen.

An important aspect of this is that the speakers of these languages are not just passive recipients of knowledge generated in the geographical north. They can also contribute their own knowledge. This also touches on the notion of cognitive justice as developed by Shiv Visvanathan in The search for cognitive justice

Cognitive justice is not a lazy kind of insistence that every knowledge survives as is, where is. It is an idea which is actually more playful in the sense the Dutch historian Johann Huizinga suggested when he said play transcends the opposition of the serious and the non-serious. Play seeks encounters, the possibilities of dialogue, of thought experiments, a conversation of cosmologies and epistemologies. A historical model that comes to mind is the dialogue of medical systems, where doctors once swapped not just their theologies but their cures. As A. L. Basham put it, the dialogue of medicines, each based on a different cosmology, was never communal or fundamentalist. It recognized incommensurability but allowed for translation.

This is a viewpoint which has been taken up in what is called Open ICT for Development, where “openness” is understood to include the the participation of communities in the governance of their own lives.

So what I found out in the aftermath of Wikimania is the question: Does Wikimania save lives? Can it help people get together and come up with practical methods by which people get in touch and existing initiatives can find that they are taken to a higher level? Will it have an affect in this example and save lives? So in this sense Wikimania is not over. It’s legacy depends on what action people take in its aftermath.

So I am writing this blog because I want you to see if there is something you can do to help either the Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team or the Translation taskforce find more support for their projects in fighting Ebola.

4 thoughts on “Does Wikimania save lives?”