You can tell Europe to help protect street photography

After last year’s drama in the European Parliament about “freedom of panorama”, the EU is consulting on how the law should change.

Article by Owen Blacker

Article by Owen Blacker

Think about the state of digital photography 15 years ago, on 22 May 2001 say. It’s about a week after Mark Zuckerberg’s 17th birthday, a few years before Flickr, Instagram is almost a decade away and most people haven’t even heard of DSLR cameras — the first consumer-targetted DSLR, the FinePix S1 Pro, was only launched just over a year earlier.

Obviously, I didn’t pick that date at random — that’s when the Copyright Directive (2001/29/EC) was made, entering into force one month later. That’s when European copyright laws were last set in aspic.

Clearly, then, it’s well past time to update it to account for the Internet era — a time when we’re all creating content, rather than merely consuming it.

Since being elected as an MEP for the German Pirate Party in May 2014, Felix Reda determined to make copyright reform his focus for the legislative session; that November, the Parliament set up a review of the Copyright Directive, for which he was named rapporteur. Reda’s annotated draft report is online and is a great, approachable read for anyone interested in copyright reform — it walks the line between pragmatic and radical very well.

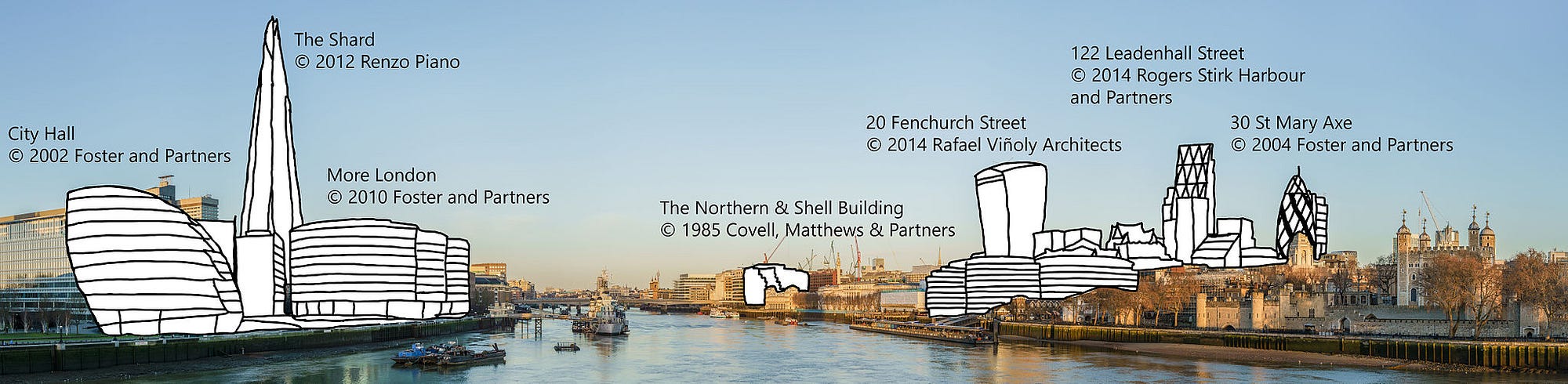

One of the more obvious areas where there are differences across the European Union is in something called “freedom of panorama”. This term refers to an exception in copyright law that says that photographs of works permanently in public spaces — buildings and sculptures, for example — do not need a licence from the copyright-holder. The team at #FixCopyright have put together a video explanation here:

Generally, European Union legislation seeks to “harmonise”, to create a common basis of law across the the common market. One of the things highlighted by the debates in the European Parliament last year was the difference in panorama rights across Europe.

Here in the UK, I can take a photograph from any public street and know that the presence of a building or item of public art cannot pose any copyright claim — I could sell that photo without issue and I can share it with a Free licence.

In France or Belgium, however, those public works of art have a copyright so, for example, images of the Atomium in Brussels are subject to rights held by the litigious heirs of André Waterkeyn until 2076, a full 70 years after his death; SABAM, the Belgian collecting society, zealously pursues those rights. The image at the top of this article is a photo of the dancing figures in Luxembourg’s Theaterplaatz, redacted to protect Bénédicte Weis’s copyright, valid until 70 years after he passes away. Iceland has restricted panorama rights too — there are no pictures of Hallgrímskirkja on Wikimedia Commons, as it is under copyright there until 2021.

Cross-border publishing confuses matters further — I’m a British citizen in the UK writing this on a website hosted in the Cloud by a company registered in California; the header image is a photo of a work in Luxembourg taken by a German domiciled in Switzerland. This is part of why the EU prefers to harmonise rules, rather than just to apply “country of origin” rules to allow different restrictions to apply in different places.

The image rights from public art really are “gleanings from the field” — they are marginal to the creators of new buildings and new art but they’re ofimmense value to the ability to publicly depict and discuss these works.

Freedom of panorama allows us all to take and publish photographs of buildings and monuments in public places — as celebrated in the Wiki Loves Monuments competition every year, as well as many books with author-supplied photographs, for example. Without that freedom, full permissions, clearances and royalties need to be negotiated for every video, photo, painting and drawing with potential commercial use.

As merely one example of why this is a big deal, Wikipedia does not accept images unless they can be reused for any purpose. The English Wikipedia’s policy on non-free content explicitly only allows images on licences that meet Wikipedia’s definition of “free” use, disallowing images that are only available for non-commercial use; the Catalan and Italian policies are similar. By comparison, the Spanish and Hungarian Wikipedias have a policy of only using Free images. Wikimedia Commons has a category full of deletion requests that relate to FoP, with over 4500 images having been deleted; there have been nearly 100 images deleted of the Louvre Pyramid alone. There are 221 censored images of European works in the appropriate categories on Commons.

“Non-commercial” restrictions seem like they’re only be a problem for companies who want to make money by selling photographs. But in practice, the distinction between commercial and non-commercial is much more complicated. Sure, you probably won’t actually get in trouble for posting holiday snaps to Facebook (§9.1 of their Terms say you give them permission to use your images commercially and §5.1 says you’ve cleared the rights to do so) but, to quote Felix Reda’s blogpost (with his emphasis) from last year:

It is far easier to transgress the limitations of a non-commercial restrictions than commonly understood. … If there is a consensus on this matter, it’s that the realm of commercial usage is entered long before a person makes a profit. You can expect your personal website to be considered commercial if you have advertisements or a Flattr button or other micro-payment service in use, even if you make a lot less money than you pay for hosting your website.

This isn’t even something that creators are calling out for, as Reda wrote in his follow-up piece, many creators’ organisations across Europe were quick to condemn the amended plans to restrict FoP, with the Royal Institute of British Architects among the first to denounce the proposals.

Of the 7 EU countries where architects and visual artists earn the highest incomes, 6 have full and unrestricted freedom of panorama (Luxembourg, the exception, is the second-richest country in the world by GDP PPP). And creators aren’t making these works ignorant of their destination — it is not the public space entering the artist’s atelier, but the artist’s work being presented in a public space.

Felix Reda’s original draft report proposed extending freedom of panorama across the Union, but an amendment was made in committee that could have threatened our right to take photographs in Europe if they included buildings or street art that’s still in copyright.

After over 500,000 people signed a petition asking MEPs to reject the anti-panorama amendment, it was defeated overwhelmingly and the final report avoided mentioning freedom of panorama altogether, by way of a compromise.

This was an “own initiative” report from the Parliament, so had no legislative weight itself but in December the Commission outlined its proposals “to broaden access to online content and … modernise EU copyright rules”. These proposals contained several changes — some of which have already been watered down, such as content portability, where they were originally proposing that I could watch BBC iPlayer and Netflix UK when on holiday within the EU but have backed down in the face of pressure from rights holders. Importantly, though, the Commission has included a consultation on freedom of panorama.

Since then, proposals have also gone to the Belgian and French parliaments to extend freedom of panorama, though the Swedish Supreme Court made a frankly bizarre ruling that, despite their panorama law, a Wikimedia Sverige website was not allowed to collect together photos of public works of art online. There are certainly problems with the French proposals, which are overly restrictive, but that the French Senate approved a pro-panorama amendment at all is a sign that the mood is changing in the more copyright-conservative countries in the EU.

For once, this isn’t something where you need to write to your elected representatives. That’s one for another time. But there is a consultation being held by the European Commission; the important thing for now is to be heard.

There is a response form on the EU’s consultation website. Alternatively, there’s an online form from the #FixCopyright team to guide you through the questions.

The EU consultation closes on Wednesday 15 June

If you would like some help with how to respond, there is a response guide from Wikimedia, with their answers available to see.

Speak up now to tell the European Commission that street photography is important and brings its own benefits — and, as always, tell everyone you know!

This article is dedicated to the public domain under the terms of the Creative Commons Zero licence. Please translate, copy, excerpt, share, disseminate and otherwise spread it far and wide. You don’t need to ask me, you don’t need to tell me. Just do it!

One thought on “Speak up for open knowledge and a free internet: Freedom of Panorama Consultation”