By Martin Poulter, Wikimedian-in-Residence at Bodleian Libraries

By Martin Poulter, Wikimedian-in-Residence at Bodleian Libraries

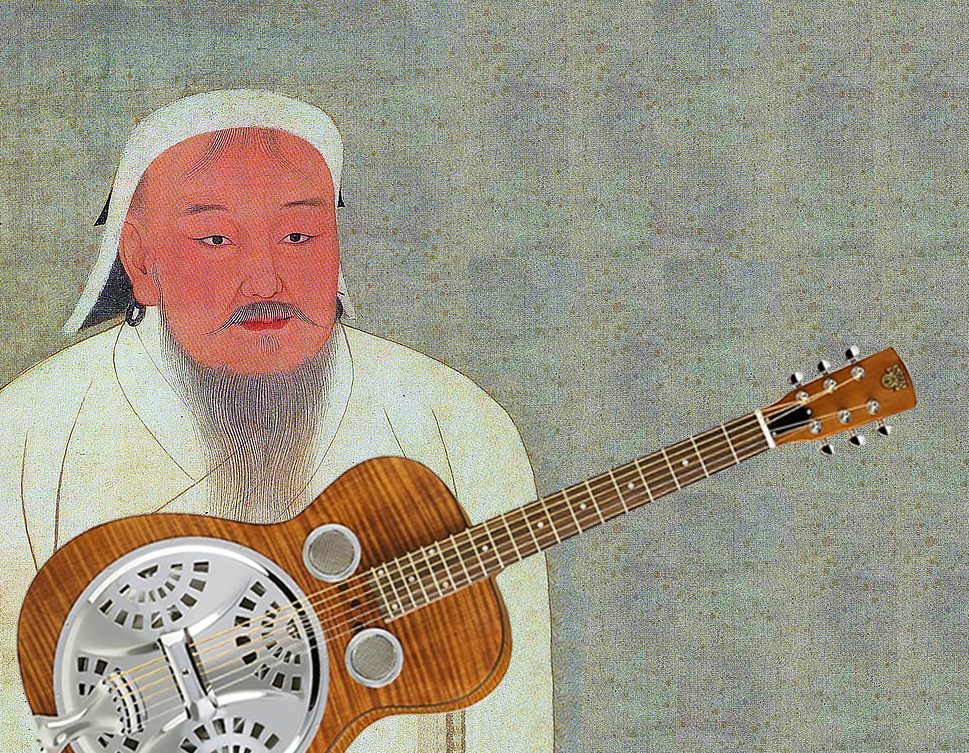

Wikipedia has more than five million articles in its English language version. No article is an island: with few exceptions, they have multiple incoming links as well as multiple links to other articles. Articles connect in a web, or like the cells in a brain. Take two widely different articles—say, Genghis Khan and Resonator guitar—and there is likely a path from one to another, but it will take quick thinking and ingenuity to find it. This is the idea behind Wikipedia racing.

A race can involve any number of players. At their computers, they “get on the starting line” by finding the start article on Wikipedia; in this case Genghis Khan. Once everybody is ready, the target article Resonator guitar is revealed, ideally on a screen to avoid it being misheard. There are variations of the rules, but in a straightforward example, the winner is the first to reach the target, only by following links in the body of the article. They cannot use the category links at the foot of the page, nor the links in the left sidebar, and definitely not the Wikipedia search box. They are allowed to use ctrl-F (command-F on Macs) to search the current page, as well as copy and paste. So if you see the word “guitar” on a page but it isn’t linked, you can save some keystrokes by copying and pasting it into the browser’s search box.

The Gregory Brothers—YouTube stars known for their hugely successful comedy songs—have made a series of Wikipedia racing videos which they call “Wiki-Wars”. They add post-match interviews, over-the-top graphics, and hilarious in-character commentary.

Ewan McAndrew and I ran a session on games at this year’s Open Educational Resources conference and discussed Wikipedia racing as an educational activity. It helps that players can reflect and discuss at the end of each round: the browser history (click and hold the back button of your web browser) show the articles visited in sequence. So players can easily retrace their path and analyse why their strategy won or lost.

In his keynote at the EduWiki 2013 conference, David White observed that assessment in schools and even universities usually assumes a scarcity of information; a scarcity that Wikipedia and other online resources have ended. Much more relevant to today’s world are overwhelming excesses of information and of options, where a person has to quickly evaluate the situation and make a choice. White challenged the audience to devise assessments that encourage the skills of leadership, including asking questions rather than just answering them.

While I wouldn’t be happy to see students sitting Wikipedia races for their university grades, it’s an activity that tests the skills White was talking about. Since the Open Educational Resources conference took place in the London district of Holloway, we got our audience to race from the Open educational resources article to Holloway, London. Success often involves moving from the starting article to a broader, more abstract concept, then zooming in to specifics to reach the target. London can be thought of as an aggregation of boroughs and districts; as an example of a large city, a capital city, or a city built on a river; or as the location of many notable events. Any of these facts might help with the race. A good racer will think of an article at multiple levels of abstraction at the same time.

A wiki race is not a situation where the teacher has “the answer” and the learners either find it or not. There will be an astronomical number of “correct” answers in the form of pathways from one article to the other, but most are prohibitively long. The players need to devise a strategy, carry it out quickly, and change tack if they do not make progress. They may well discover a path that is quicker than any the teacher had thought of.

Subject knowledge certainly helps in wiki racing, but not decisively. If you know that one of the central documents of the OER movement is the Paris OER Declaration, then you have a short-cut from Open educational resources to Paris and thence to London. If you don’t know this but can skim an article, find links, and judge which ones will take you towards the target, you can still win.

Having observed races on video and in real life, what stands out is a common theme in the psychology of problem-solving. People can get stuck in an inappropriate mental set: a set of assumptions and labels that they bring to the problem. Getting stuck in two-dimensional thinking for a puzzle that requires three dimensional thinking is an example. Progress involves changing a mental set that is no longer useful: people who can jump between ways can be very effective problem solvers. In wiki racing, people can hatch a plausible strategy but the link that they expect to see isn’t there. The rational thing to do is to backtrack and try another path, but it is easy for people to get stuck on the idea that their strategy should work. These are the players who read through same article again and again while others leap on to other articles.

Variations of the game and tips for customising are documented on a Wikipedia project page. You can choose widely different articles to make the game a test of information skills, or have similar articles (e.g. species, politicians) to make it more of a test of subject knowledge. You can make the race more difficult by forbidding the use of certain articles, or make it easier by allowing category links.

Our experience was that people found the game powerfully absorbing: it was hard to get people to stop and do something else! The feedback suggests that we showed people a different role for an educational resource such as Wikipedia: not like a book to be read from beginning to end, but like a public space in which you can run around, explore, and play games with other learners.