Wikipedia receives about 18 billion page views per month from around 1.4 billion unique devices. While many people use Wikipedia for basic research into subjects which they want a simple understanding of, Wikipedia and its sister projects also have many uses which can be useful for journalists to make part of their research process.

Traditionally, journalists, like students, have been discouraged from using Wikipedia as part of their research, but this attitude is slowly changing as people realise that while information should not be exclusively sourced from Wikipedia articles, Wikimedia projects (like Wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons and Wikidata) can be powerful tools for journalists.

Some general rules

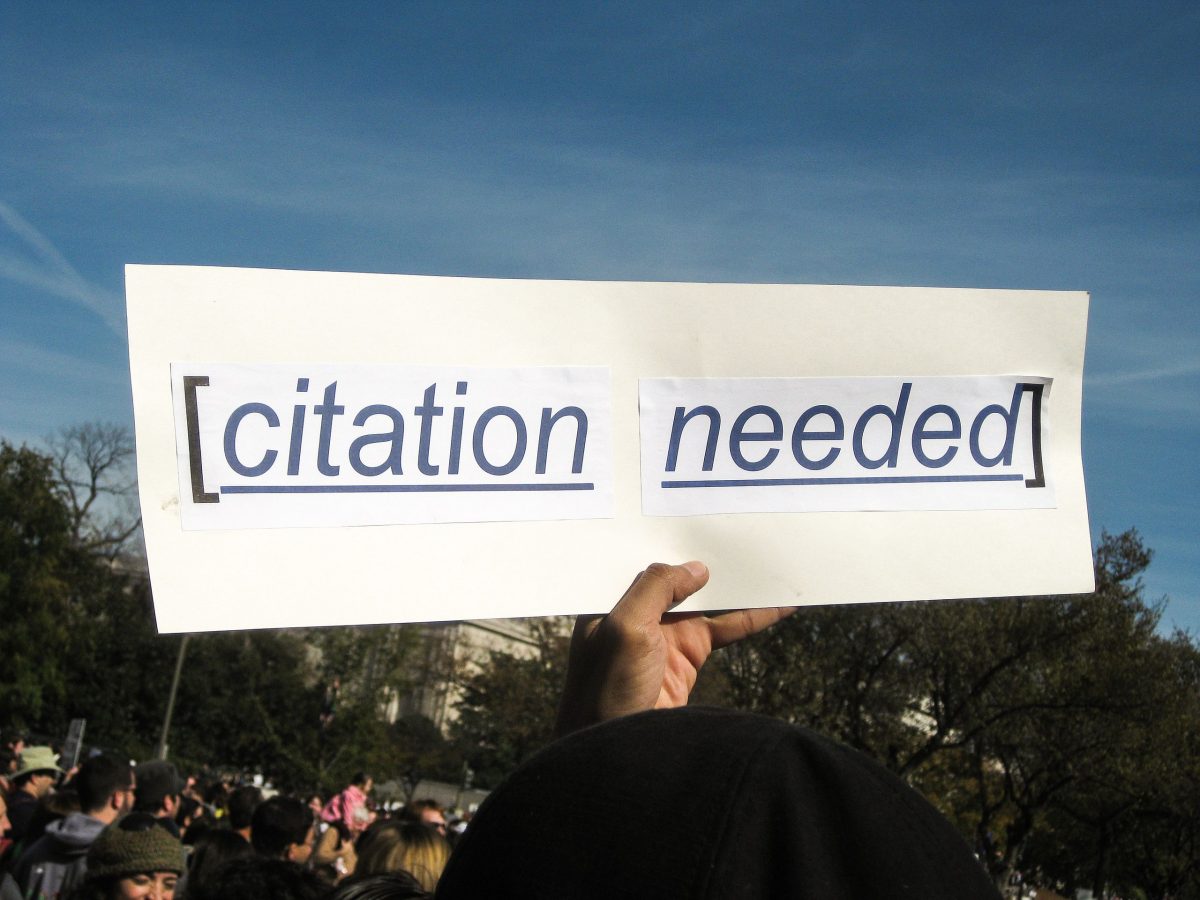

Don’t just accept facts, check the citations. Every fact on Wikipedia should be condensed from another source. Those sources go in the references list at the bottom of the page.

When former Guardian editor Paul Preston died recently, the Guardian repeated a claim in his Wikipedia page that a book he had written, The 51st State, had been made into a film with Samuel L Jackson. There was a film with that name and Jackson in it, but it was not based on Preston’s book.

This is probably the most basic point, but it’s worth reiterating. Asking a journalist friend of mine whether she used Wikipedia, I was told that nobody trusts the information provided on Wikipedia alone because the editing process is open to all. In practice however, many journalists cut corners and still often plagiarise whole sections of articles to save time, even if their managers tell them not to.

Plagiarism also breaks the Creative Commons licences that all information on Wikipedia is shared under, which state that you are allowed to reuse any of the content as long as you attribute the source. So especially if you’re a group of Japanese lawmakers on a tax-funded fact-finding trip to the US, you should avoid copying entire sections of Wikipedia to save time, as it’s very easy for people to find out you did that kind of thing.

Basically, don’t be lazy. Wikipedia’s information is transparent, and allows you to see its provenance. You might also want to check the View History tab at the top of the page to see who has been editing it and when, and look on the Talk tab to see what issues with the page have been considered by its editors.

Familiarise yourself with Wikipedia’s rules and guidelines

Only around 30% of all pages on Wikipedia are the articles themselves. The rest are the talk pages, user pages, policies, WikiProjects, Lists, disambiguation pages, Category pages and so on. The most meta level of Wikipedia’s rules is contained in what we call the Five Pillars of Wikipedia. These are:

- Wikipedia is an encyclopaedia. It’s not a soapbox, an advertising platform or a vanity press.

- Wikipedia is written from a Neutral Point of View (NPoV).

- Wikipedia is free content that anyone can use, edit or distribute. Everything is published on Open Licenses, mainly Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0

- Wikipedia’s editors should treat each other with respect and civility

- Wikipedia has no firm rules.

The next most important rules are the Notability Criteria, and the Reliable Sources guidelines, or you can check out the entire List of guidelines.

Understanding sources

One important aspect of media literacy that these guidelines can teach you is that not all sources are made equally. Wikipedia does not accept self-published sources as reliable, such as petitions, blogs and social media posts. It also discourages the use of tabloid news sources where better ones are available.

A decision taken by editors to include the Daily Mail in this list of discouraged sources made headlines last year when it was widely reported as ‘Wikipedia bans the Daily Mail’. Daily Mail sources are not banned on Wikipedia. Thousands still exist, but should be replaced by better ones if they are available.

Wikipedia is what is called a ‘tertiary’ source. It’s not an eyewitness account or opinion (a primary source), or a secondary source, which combines and discusses information first presented elsewhere. It should be a summary of the best available primary and secondary sources about a subject. Tertiary sources are not ‘academic level’ sources, so you shouldn’t cite Wikipedia articles in academic papers. You’re also not allowed to cite one Wikipedia article in another one.

With this in mind, it follows that journalists should use tertiary sources like Wikipedia as background research to understand a topic, and find good primary and secondary sources that can help them dig deeper into the subject they are researching. As Wikipedia co-founder Jimmy Wales said back in 2011,

“Journalists all use Wikipedia. The bad journalist gets in trouble because they use it incorrectly; the good journalist knows it’s a place to get oriented and to find out what questions to ask”.

Science and medicine

Not all parts of Wikipedia are the same. Much higher reliable source guidelines exist in the scientific and medical areas of Wikipedia, where generally only well known journal articles will be accepted.

I once tried to improve the article on Water Fasting, in response to someone on Twitter saying it wasn’t very good. It’s not very good, but that’s because there have not been any reliable medical studies done on it which have been written about in reliable medical journals, so there’s not much that can be said. My edits to enlarge the page with information from articles in the Huffington Post and other sources all got deleted.

Once again, one of the best ways to find out how Wikipedia works is simply to edit it. This fact is somewhat similar to the commonly referenced idea of Ward Cunningham, inventor of the wiki, who said that “the best way to get the right answer on the internet is not to ask a question; it’s to post the wrong answer.”

This discourse between people with competing views generally helps to make Wikipedia more reliable over time: as articles are edited by more and more people, the information becomes better, as a Harvard Business Review investigation discovered in 2016.

Tools

Because all of Wikipedia’s data is open and searchable by machines, there’s lots of interesting things that people are doing to make use of the data. Some bots scan the list of edits for vandalism, or people editing from IP addresses known to come from the UK Parliament or US Congress. People have also made Twitter accounts that automatically publish these edits on Twitter. Here are a couple of them:

Parliament Edits – https://twitter.com/parliamentedits

Congress Edits – https://twitter.com/congressedits

Maybe you want to find out what GPS data exists on Wikipedia and its sister sites in a particular area. Check out the WikiShootMe tool to see Wikipedia articles, photos from Wikimedia Commons and data from Wikidata with GPS coordinates displayed on an OpenStreetMap.

Another useful thing you can use to see data about Wikipedia pages that is not immediately obvious is the Page View tool. Every Wikipedia page has a link on the left hand side under Tools that says ‘Page information’. Clicking this link and then scrolling to the bottom of the page, you will find another link called ‘Page view statistics’. This will take you to a tool where you can see how many visits that page had within a given time period of your choosing. Using this tool can provide useful insights, such as the fact that the biggest spike in views to the European Union article was on the day following the Brexit referendum.

Wikimedia Commons and Wikidata

When I was a freelance journalist, one of the most useful aspects of the Wikimedia projects was the free image database, Wikimedia Commons. All of Wikipedia’s media files are hosted there, all under Creative Commons attribution licenses, meaning that you can reuse or modify them in any way you like, as long as you credit the original author of the media. Look in the details below any image to see the creator or user who uploaded the file. Your credit should look like this ‘[Image name] by [username], CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons’.

To search Commons for images, try typing Category: into the search box, followed by a type of image you’re looking for. You can then search for images tagged with this category. Alternatively, try looking through the list of Featured images or quality images for something to use.

Wikipedia and its sister projects are huge and complicated, and there are so many ways that they could be used by journalists that there are probably many things missing from this list. If you’re a data journalist, for example, and want to do complex data queries, I would suggest learning how to use Wikidata. You can find tutorials online like this one or this one to show you how to use the Query Service to search the data.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1jHoUkj_mKw

If there’s one final piece of advice I would like you to remember, it’s that all media is made by people, whether it’s on the BBC, YouTube or Wikipedia. The only way to really understand a platform like Wikipedia is to get involved in editing it. Understanding how it works should allow you to get the most out of it, and to avoid writing simplistic articles like I often see on sports websites, about how X football player’s Wikipedia page was HACKED by fans of an opposing team. Editing a Wikipedia page is not hacking it. It’s what you’re supposed to do to it. Pages get vandalised all the time, and there are sophisticated ways that have been developed for reverting and flagging vandalism that ensure it doesn’t tend to last for long.

You should also remember that Wikipedia is still a work in progress. That’s why the logo is a puzzle piece globe of different languages. The majority of people editing Wikipedia are still white, male, and from the global North, and this affects the content on the sites. There are lots more articles about military history, WWE wrestlers and men in general than there are about women, queer or non-European people or history. Part of being a good journalist is being aware of these biases, and taking them into account in your writing.

Thanks for reading this guide, and I hope you have found some of it useful!