By Jason Evans, Open Data Manager at the National Library of Wales

10 years ago I turned up for my first day at work as a Wikipedian in Residence at the National Library of Wales. I had a 12 month contract and instructions to hold 3 Wikipedia Edit-a-thons, share some images openly to Wikimedia Commons and monitor the impact.

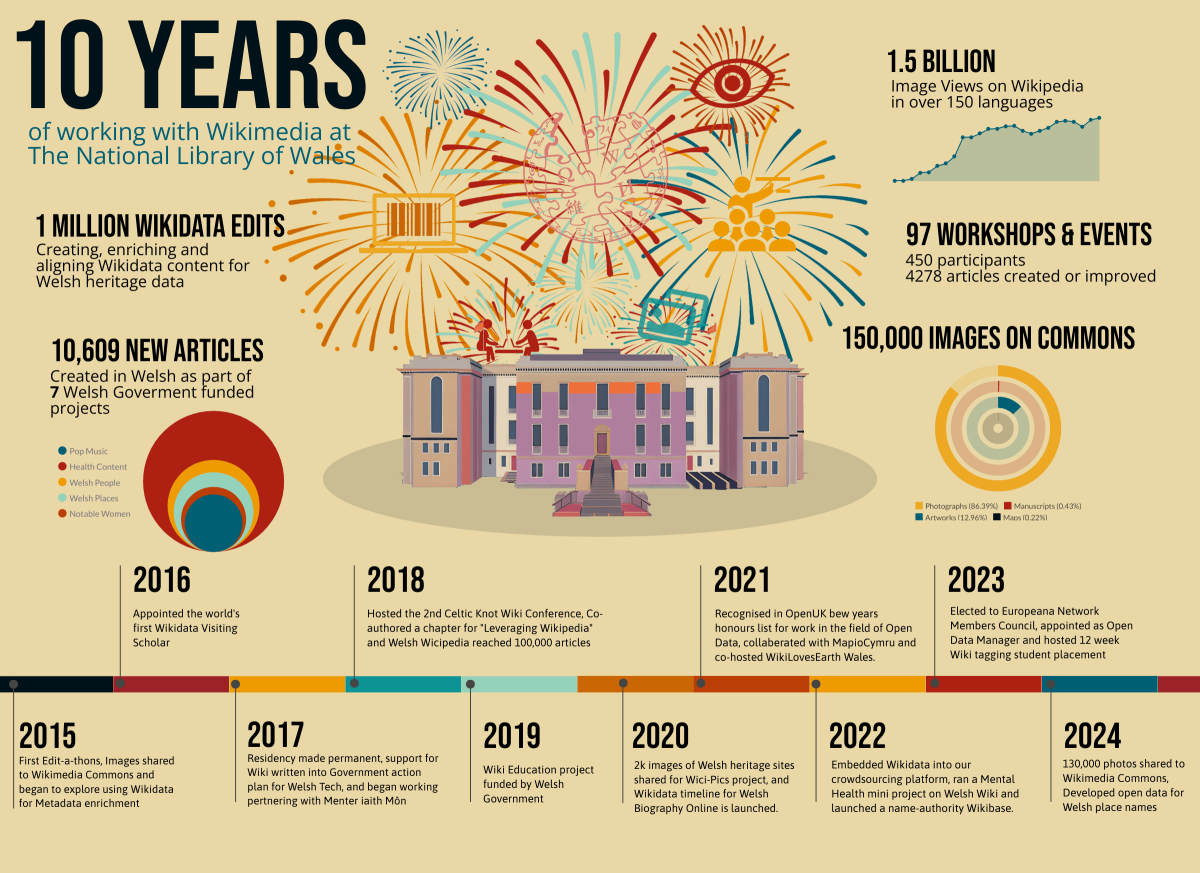

A decade later and I’m still here! I’ve transitioned from Wikipedian in Residence to National Wikimedian, to Open Data Manager, with Wikimedia projects still firmly at the heart of what I do at the Library. We have shared over 150,000 images to the Commons with 1.5 Billion views. I’ve held 97 workshops and edit-a-thons, delivered 10 grant funded projects and overseen the creation of thousands of new Wikipedia articles, mostly in Welsh. In this time the role has evolved dramatically but the core principles of openness, engagement and innovation have remained unchanged.

Reaching this milestone is an opportunity to reflect on the achievements and challenges of the last 10 years, and to think about what the next decade might look like in a rapidly changing digital landscape.

On a personal level the role has certainly helped shape me professionally and as a person. I’ve become a passionate advocate for open access, for the Welsh language and for open knowledge. When I took up the role, my skills lay mainly in research but I’ve learned a huge amount about community building, about impact and evaluation and my technical skills have increased dramatically. I’ve taught myself how to bulk upload to Commons and Wikidata, how to write a SPARQL query and even how to run python scripts and bots, which is incredibly empowering. But the area I love most is strategy. It’s taken a while, but I’ve learned to think strategically about my work; how tasks and projects help build towards broader goals and how to maximize impact, or public benefit, through my activities.

I think it’s important to acknowledge that none of this would have been possible without the continued support of management at the National Library. In my time here I’ve seen many brilliant residencies come and go and the Library’s commitment to this work, long term, is something not often seen in the GLAM sector. I’ve also been given the freedom to try things out, to explore leads that sometimes go nowhere and to implement new ideas. About 6 months into the residency I remember being introduced to Wikidata for the first time at Wikimedia UK’s old London Office. I immediately saw huge potential for describing and linking cultural heritage data and was given the time to explore this further. As a result we became an early adopter of Wikidata in the GLAM sector, hired the world’s first, and only (to my knowledge) Wikidata Visiting Scholar. The library has contributed millions of edits to Wikidata, expanding linked open data about Wales and its people. Time and time again I’ve been given the freedom to design my own projects and to travel to share skills and learn from the global community. I’m certain that a more rigid, micro managed approach would have seen the work and the funding dwindle away early on.

In terms of why the library has continued to fund this work, there are a number of reasons. Firstly impacts such as massive image views on Wikipedia, public engagement and support for the Welsh language align with the institution’s core values. Around 5 years ago we started counting views of Wikipedia pages containing our images as a key performance indicator, reporting quarterly to the Welsh Government. I’ve built relationships with many other institutions through our Wiki work, from universities and GLAMs to governing bodies. In year two we also formed a close relationship with the Welsh Government around their work to support Welsh language technology and education. And all this has led to a number of grant funded projects and collaborations in the digital scholarship space – effectively subsidising the cost of my role, whilst building partnerships, communities and improving Welsh knowledge online.

To some extent the longevity of my residency is probably also down to the ever evolving scope of my work. I’ve always tried to observe how people want and expect to be able to access knowledge and adapt my work to ensure the library is supporting the creation and maintenance of knowledge in that space.

Early in the residency the focus was very much on Wikipedia. That is where people go for information, so that is where we should be; training new editors, sharing our collections and our knowledge. Many of our early projects focused on these goals. We ran a project on Welsh Pop Music, creating Welsh language articles about Welsh singers and bands. We even convinced a Welsh record label to share short clips of songs, and album artworks to Wikimedia Commons. Another project which I’m particularly proud of focused on creating health related content in Welsh. Welsh Wikipedia lacked key articles about diseases, treatments and mental health topics. I remember a conversation with a first language Welsh speaker who had suffered with depression and anxiety telling me that she was volunteering to write relevant content so that others didn’t have to read about their diagnosis in their second language. For me that was a powerful reminder of why supporting Wikipedia in smaller languages is so important.

In 2018, we hosted the second Celtic Knot Conference at the Library. Supported by Wikimedia UK and originally aimed at engaging small Celtic languages on Wikipedia, the conference has grown in scope to a global Wiki conference for small and minority languages, with participants from all over the world.

Education has also been a focus over the years. Young people in particular rely on the internet to learn. Early in the project educators were often wary of having anything to do with Wikipedia, but we’ve seen a real transformation, with most now embracing Wikipedia, accepting that students are going to use it anyway, and engaging with it to help them understand how it works and how to use it responsibly. In 2019, with funding from the Education Department we developed the “WikiAddysg” (Wiki Education) project, aimed at improving Welsh Wikipedia content related to the secondary school History syllabus in Wales. We consulted with teachers, secured open access to Welsh learning resources from a number of organisations and hired a former history teacher to help us adapt the content for Wikipedia. We even commissioned short educational videos to compliment the articles. For many years we’ve also supported Menter Iaith Môn’s Wikipedian, who has been running Wiki events in schools in Anglesey, North Wales. Wikimedia UK has been super supportive in securing a foothold for Wikipedia in Welsh education and I’m full of hope that this area of work will continue to grow.

We continue to support Wikipedia with regular edit-a-thons, tailored volunteer training and research into automated methods of creating Welsh language articles. However, over time our focus has shifted to encompass data. Over the last decade, the value of open data for research, learning and commerce has been increasingly acknowledged. It allows for siloed datasets to be interlinked, it allows communities to collaborate to improve and enrich knowledge as data and helps power new and innovative tools for knowledge exchange. And this was before the AI boom, where we are increasingly aware that computer models are only as good as the data which powers them.

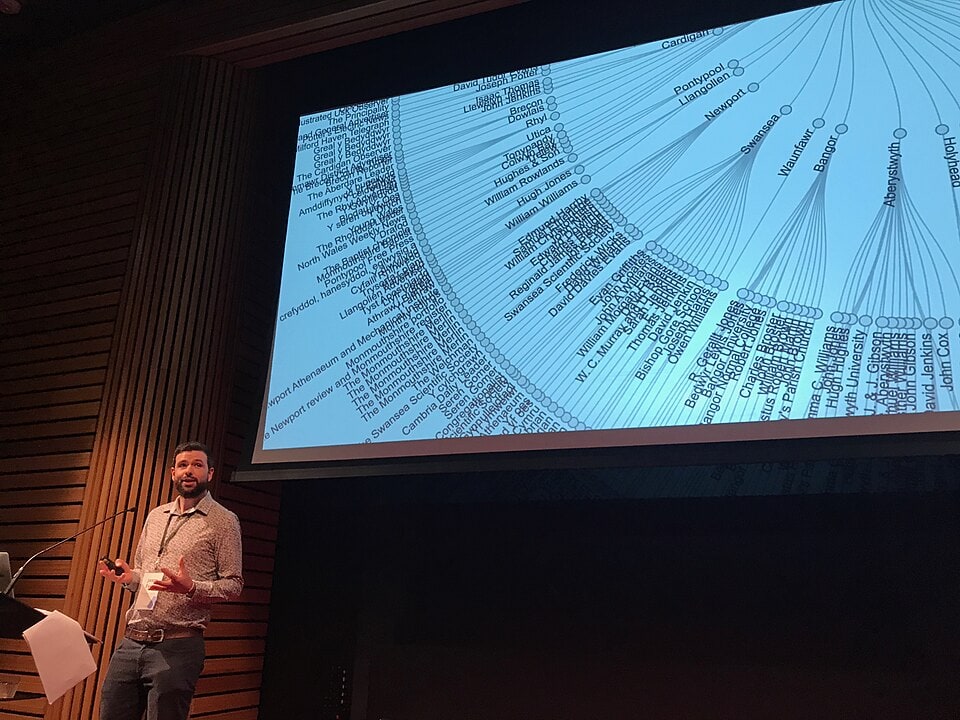

I think it’s fair to say that Wikidata has become the largest collection of open cultural heritage data the world has ever seen. You can look up an artist, a poet or scribe and see links to their archives in institutions all over the world, or see an artist’s life work in one place. Linked Open Data is now seen as the gold data standard by many – a modern data infrastructure for cultural heritage data with common standards and structure. Like many public sector institutions we have faced constant cuts to our budget, and platforms like Wikidata and Wikibase have been a way for us to begin the process of modernising our data, of linking it to other datasets in Wales and beyond with minimal investment and in an inclusive, open and collaborative way.

Last year, we launched our Welsh Name Authority Wikibase, which already links over 100,000 Welsh people and places across collections and institutions. We’ve also worked closely with the Welsh Language Commissioner since 2023, aligning their data to Wikidata and other Welsh heritage data. Wikidata lets us do this bilingually, so we can make our datasets available in Welsh for the first time. We’ve already seen the value in investing in this Open Data. The Welsh Government, the BBC, The Welsh Biography Online and Mapio Cymru (Welsh OpenStreetMap) have all used our data. We helped improve a popular daily Welsh language quiz app that uses Wikidata to create a huge bank of questions, and what3words launched a Welsh language edition thanks in part to Welsh language Wikidata labels.

Just last year, the Welsh Language Commissioner launched a new website for their database of standardized Welsh place names, and thanks to the alignment with Wikidata they’ve been able to include images and sound clips from Commons and links to Wikipedia articles, creating a rich user experience. I’m particularly fond of this collaboration as an example of community and institution working together. The idea of combining authoritative data with crowdsourced data not only leads to better tools and services but fosters an inclusive space where everyone can be empowered to contribute their voice, their knowledge and their passions.

There have, of course, been challenges and frustrations along the way. Many fixed term residents finish their posting without having affected fundamental changes within their host organisation, and that’s not to say that these residencies were a failure, just a reminder that the wheels of change move very slowly in many GLAM organisations, and ours is no different. Before I was appointed the library had made a bold policy move (bold at the time) by relinquishing any claim to digital reproductions out of copyright works, and it was this decision which allowed me to get right to uploading content to Commons. But shifting the organisational culture to an “open by default” mentality is an ongoing and occasionally circular conversation. Much of the reluctance to be more Open, in the library and other organisations I’ve worked with boils down to budgetary pressures, a lack of confidence in making big changes to long established systems and sometimes just a difference in interpretation of licensing and copyright law. I’m confident though that things are moving in the right direction, highlighted by our recent release of over 120,000 photographs to Commons, documenting Welsh life in the 1950s and 60s.

The Wikiverse can also be a tricky place to navigate at times. Tools for uploading images and monitoring impact tend to break from time to time, and when they are replaced with new ones the learning process starts all over again. Most of these tools only exist at all thanks to dedicated volunteers, and it would be great to see more support from the Wikimedia Foundation in creating a stable toolset for partner organisations. Once again though it feels like things are now moving in the right direction.

Of course, the biggest challenge facing Wikimedia UK and the wider Wiki movement is how to respond to the rise of Generative AI. It’s also a topic taking up more and more of my time. How good will it get? And how soon? How can we correct mistakes and tackle inherent bias? How do we ensure smaller languages are not left behind? These are just a few of the questions I’ve been asking myself. So as I look to the future I’m left thinking that perhaps the golden age of Wikipedia as a destination has passed. But that doesn’t mean it’s any less important, especially in smaller languages. If, as a society, we continue to value the vision of free knowledge for all, the Wiki projects will continue to be the most effective way of achieving this, and the most effective way of feeding new knowledge into the digital space.

I don’t think anyone really knows how the next ten years will play out but I hope we can continue to build on the momentum towards an Open society and to use new technologies for good; for sharing knowledge more widely in all languages, for reducing bias and for linking our knowledge together across institutions, sectors and cultures. For as long as Wikimedia and its volunteers represent these values I’m confident that Wikimedians in Residence will continue to further the cause, driving digital transformation in their host institutions which benefit society as a whole.