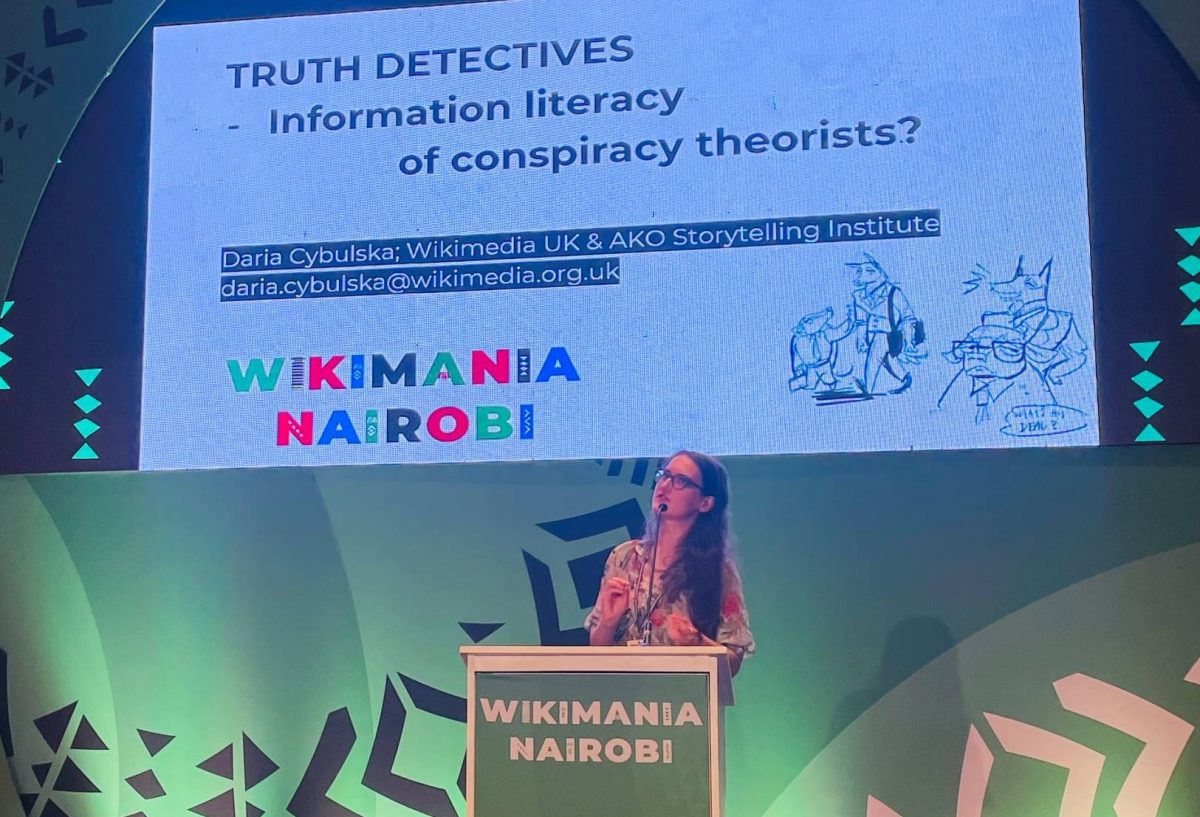

Daria Cybulska (Poland/UK) is the Director of Programmes and Evaluation at Wikimedia UK, leading programmes and advocacy for knowledge equity and information literacy. She designs projects and partnerships for digital human rights on Wikipedia. She shapes how Wikimedia UK can support a democratic and empowered society in the UK. Daria is a trustee at Global Dialogue, a platform for human rights philanthropy, and in 2023/24 was awarded a Churchill Fellowship, investigating Central Asia’s online civil society and its resilience responses to a shrinking civic space. She was also a fellow at the AKO Storytelling Institute, based at the University Arts London. The Institute is investigating the theory and practice of storytelling-for-change across disciplines – art, campaigning, social impact, research, philanthropy. At AKO Daria created a narrative shift project on information literacy of conspiracy theorists.

Wikimedia UK demystifies and drives engagement in open knowledge, as the national charity for Wikipedia and the other Wikimedia projects. We have been delivering education activities for over ten years, with an explicit focus on the use of Wikimedia as a tool to develop information and media literacy skills. Our programme takes place online and in schools, universities, museums, libraries and community settings.

Our research shows that learning to contribute to Wikimedia helps people better understand, assess, and navigate online information, with participants in our programme reporting increased confidence in their digital skills and media literacy. Learning to edit Wikipedia gives participants a chance to practice understanding content, verifying information, applying critical thinking skills, reflecting on one’s role within the online spaces, and using collaborative and group learning skills.

Equipped with the essential tools to navigate the digital landscape, individuals are also empowered to become active contributors to the online world and increase their civic participation; strengthening UK society.

While Wikimedia UK’s work demonstrably develops information literacy within its programme participants, this development happens with a strong focus on the intellectual, cognitive skills of the individual learner. In contrast, my research is inviting people to explore how emotion shows up in critical thinking, and how, if emotions are not considered in information literacy education, this can derail the learning process, while also fueling polarisation.

We explore this by looking at misinformation and conspiracy theories. Conspiracies can drive polarisation in society and divide how we think and support a situation where we don’t even share the same view on reality. However, by promoting simplistic arguments about being cleverer than others, information literacy educators can encourage self-righteousness and possibly even closed mindedness, making it hard to consider or connect with those with different values and ideas (and conversely, the conspiracist side talks about others in a dismissive way too).

If we resist taking a disdainful view towards those believing disinformation or conspiracy theories, and instead focus on recognising a common love of research or skillful use of emotions, we may be able to actually push against some of the polarising effects of misinformation.

There are things that information literacy educators and conspiracy theorists have in common. These similarities show up in phrasing used commonly by both sides:

1. Methods for assessing information – check sources, don’t immediately trust what you see, connect the dots, think about who funded the information, do your own research, etc.

2. Personality traits and features of those who ‘know better’ – love for research, desire to know the truth.

3. Active participation in learning.

What’s markedly different though is the use of emotion – in the conspiratorial realm, the research approach includes a strong element of excitement of investigation or discovery, but also of anxiety about the world. There is also the desire to belong (to a group that’s ‘in the know’), satisfaction of knowing something – and of correcting or enlightening others. Then there’s a deeper set of emotions such as shame of being proven wrong or needing to change opinion, discomfort and anxiety of not being certain. Conspiracy theories themselves also hold a captivating allure – they present a coherent and emotionally charged storyline, captivating and engaging audiences.

In contrast, emotions tend to be discredited in the domain of information literacy learning, as they are deemed not objective. But emotion guides our attention, and so it is not possible to completely separate them out from the activity of learning. While the general focus of literacy education has primarily been fixated on the pursuit and validation of facts, it is crucial to address the emotional dimensions entwined within these processes. We also need to consider how to confront and mitigate the emotional elements that propel individuals towards embracing disinformation.

One aspect emerges as absolutely crucial: complexity resilience – being more comfortable with an increasingly ambiguous, complex, and difficult world. Rather than simply offering definitive answers or actions (like conspiracies do), educators should seek to emphasise the proposition of diverse ideas, perspectives, and narratives – and be comfortable with that diversity and complexity.

Teachers hold an important key in guiding information literacy, but cannot do it alone. A multidisciplinary, collaborative approach is called for – including a psychologist to account for the emotional layer (both for learning, and teaching), librarian to guide how the knowledge ecosystem is built, and a journalist with reliability strategies.

This could be considered while we debate the overall shape of information literacy education in the UK. Wikimedia UK sees the current provision for the development of media and information literacy skills within English secondary schools as patchy at best. From our experience we hear that teachers themselves may never have received any formal training in relation to media and information literacy. But it is more vital than ever that young people have the knowledge, skills and confidence to question what they see online, whilst understanding what constitutes reliable, trustworthy information.

We welcome comments on how the approach to ‘complexity resilience’ and the role of emotion in education could be included in teaching of information literacy in schools, please feedback.