By Dr Richard Nevell, Programme Coordinator for Wikimedia UK

I’m a big fan of the Archaeology Data Service (ADS). Its online library is packed with digitised articles, books, and reports. Looking in from the outside I have seen its content grow and become ever more useful.

The ADS hosts a lot of data about people, places, and publications. Wikidata is an open source database in the Wikimedia network of websites; founded in 2012 it has grown to include a huge amount of information. Both sites continue to grow, and there are some points where they can complement each other.

Back in 2020, I got in touch with the ADS to ask if they could share a spreadsheet of their identifiers for individuals so that I could add them to Wikidata. Adding ADS identifiers to Wikidata entries on individual archaeologists means it would be possible to find out what information Wikidata has on these people. For the ADS, it means they can import other identifiers such as Open Researcher and Contributor IDs (ORCIDs – maintained by researchers) and International Standard Name Identifier (ISNIs – used by libraries and archives). The process of reconciling the two datasets would help with the quality of both, highlighting inconsistencies or duplications.

As a (slightly late) celebration of Wikidata’s 10th birthday, below I’ve explained some of the ways in which Wikidata has helped illuminate the ADS, and the process I followed to add the information.

What is a Wikidata item

If you’ve not come across Wikidata before, the obvious question is how is it meant to be used? The website is designed to be machine readable, so rather than containing information in prose it’s broken down into discrete ‘statements’. This means the information in Wikidata can be picked up by the likes of Google, and Wikidata can be a centralised hub for standardised information for the Wikimedia projects.

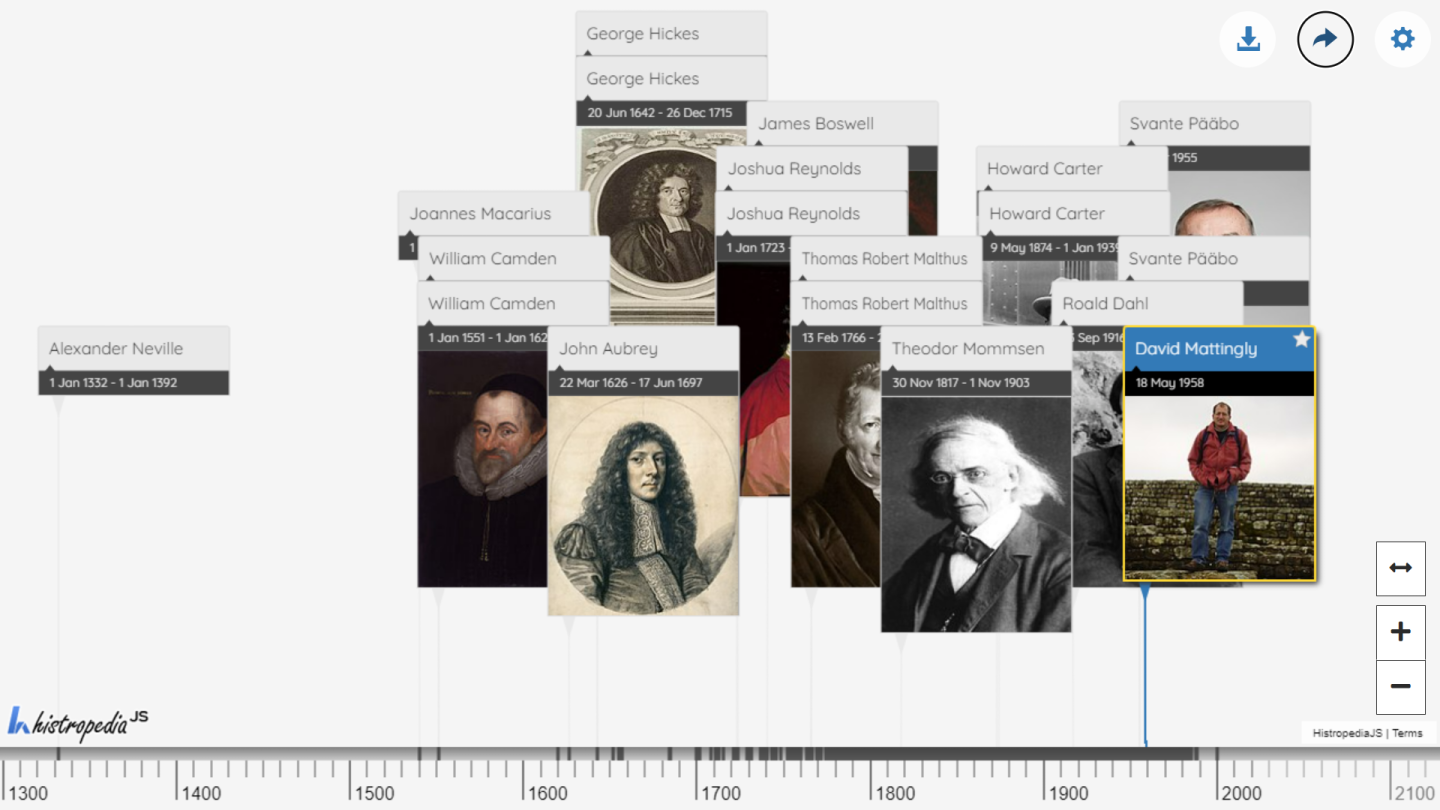

Wikipedia is available in 300+ languages which presents a maintenance challenge. For example, when a census is released Wikipedia editors have to update thousands of pages; if the data is stored centrally that makes the process dramatically easier. That’s just one application of Wikidata, other possible uses include creating interactive timelines, like this one showing folks in the ADS with a known birth and death date, and automating brief summaries of topics.

Whereas Wikipedia has articles, Wikidata has ‘items’. Each one is about an individual topic. For this blog post, that means a person can have an item about them, and a publication can have an item. They can then be linked together. Wikidata’s inclusion criteria are broader than Wikipedia’s, so you don’t need to have a Wikipedia article to end up in Wikidata. Crucially, people with Wikipedia pages will have more detailed items in Wikidata. Just take a look at the item for Ian Hodder (who has Wikipedia articles about him in 19 languages) compared to the one for Peter Arrowsmith (no Wikipedia page).

A closer look at the data

The ADS hosts scans of reports from a host of archaeological service providers in the UK and articles in county journals. Even when documents aren’t available, they still host some meta-data about the publications. As a result their data leans heavily towards British archaeologists.

You can see that when querying Wikidata’s country of citizenship data. The above buddle chart shows the citizenship for people in the ADS with an article on the English Wikipedia. 733 people are citizens of the United Kingdom, and 506 are citizens of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, though there is undoubtedly a lot of overlap. The next most common countries are the USA (115), Great Britain (65), and France (43) [full results]. You can look more widely to include anyone in the ADS dataset on Wikidata, even if they don’t have an article about them. The pattern is very similar, with the same five countries at the top.

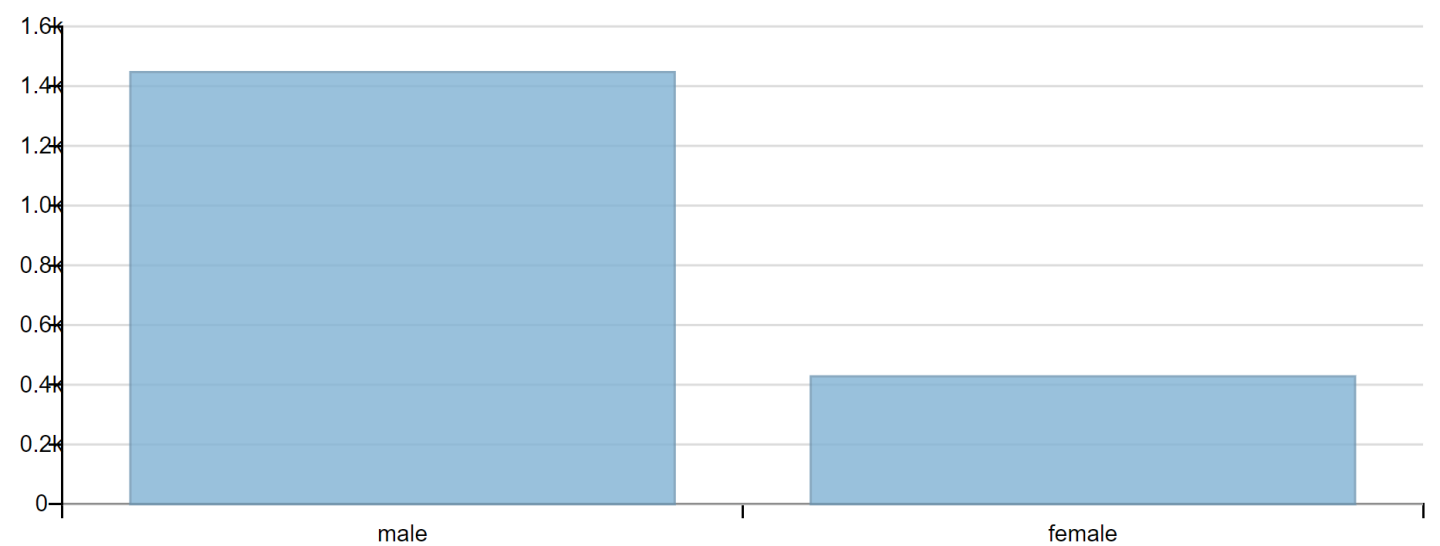

Wikipedia’s content has a gender gap: as of 24th October 2022 the English Wikipedia has 1.9 million biographies and 19.36% are about women. This is based on what is recorded in Wikidata – it’s all interconnected. Narrowing it down to archaeologists, the English Wikipedia has 5,129 biographies and 22.15% are about women. So archaeology isn’t doing too badly in the context of English Wikipedia. 1,869 of these archaeologists with biographies on the English Wikipedia have an identifier in the ADS and 22.79% are about women. The actual number will increase over time as further matches are made and new articles are created, but this likely represents the majority of the matches that can currently be made.

If we widen the search to include all the people in the ADS with a Wikidata item, 4,641 have a gender and 24.09% are female.

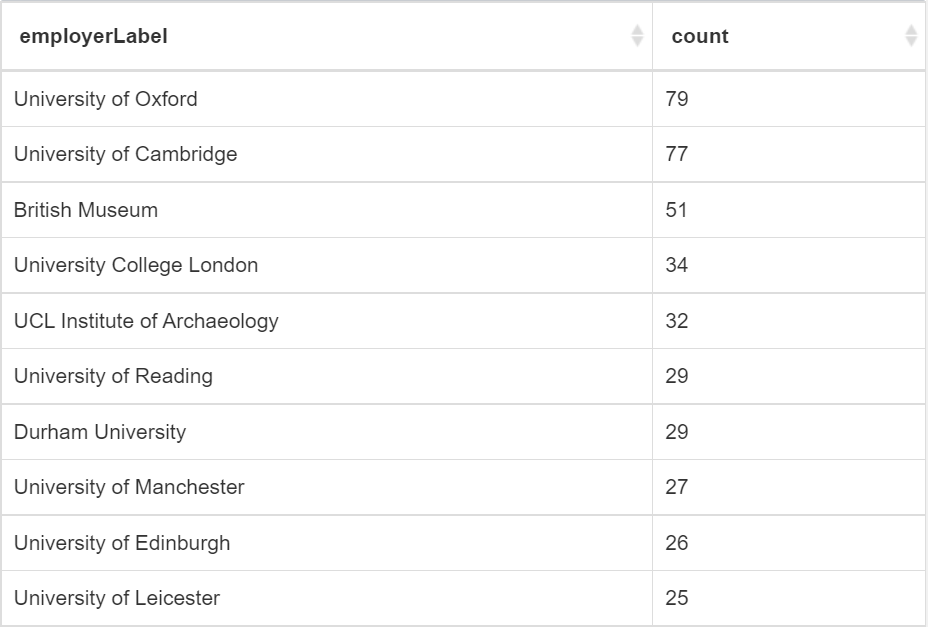

Given the UK focus of the dataset, it’s not surprising that the ten most common places of education from people in the ADS (where Wikidata has information, for people with articles in English) are all in the UK. You have to go down to 18th to find a university from outside the UK (Harvard).

Where people work is heavily skewed towards universities. Looking at just people in the ADS who have articles on the English Wikipedia, universities account for nineteen out of the twenty most common workplaces. Archaeologists in universities are more likely to end up with Wikipedia articles than folks in commercial archaeology or the museum sector. If we drop the requirement of having an article on the English Wikipedia, the results have more variety. Because people outside academia are less likely to have articles, the data available for people in commercial archaeology will be much poorer.

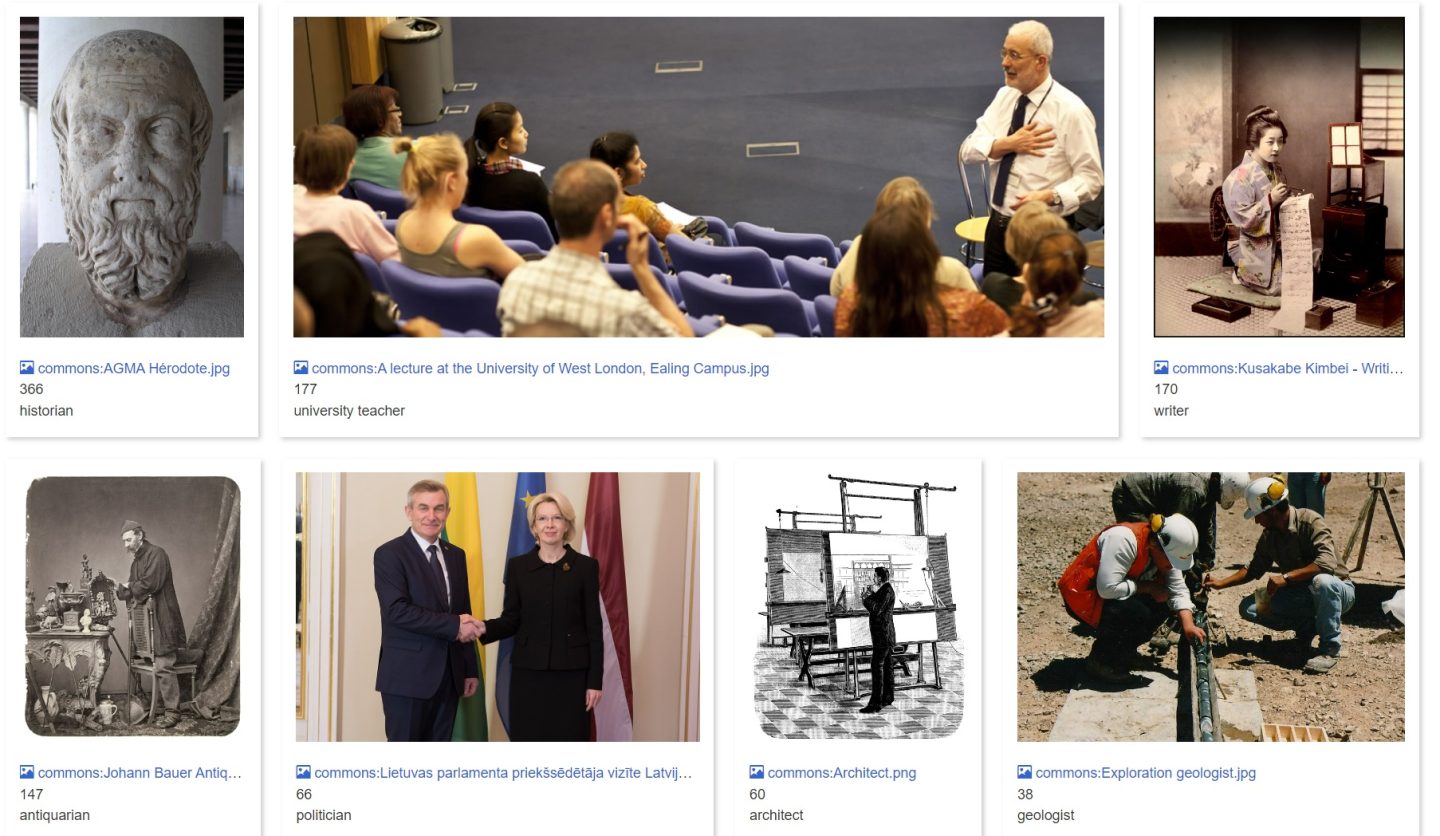

The ADS doesn’t just have entries for archaeologists. Historians, geneticists, and numismatists all appear in their dataset. The ADS even has an entry for Billy Bragg. Yes, that Billy Bragg. I double checked just in case. So aside from archaeologists, what professions do people in the ADS dataset have? For this bit, let’s look at everyone in the ADS with a Wikidata entry, not just people with articles on the English Wikipedia. It’s not surprising that a historian is the most common job amongst the dataset.

Steps to make it work

Back in 2020 the ADS provided a spreadsheet of their data, with columns for given name, surname, initials, date of birth, date of death, ORCIDs, ISNI, and the ID in the ADS database. For most people in the data set, it was a matter of name and ID in the ADS database.

The first step was adding this data to a tool called Mix’n’match. It’s a staging area before Wikidata, where information can be matched to what already exists. The idea is to add a new ID to Wikidata items where they already exist and to create new items where they don’t exist yet. If in doubt, create a new item in Wikidata. They can always be merged later if it turns out there is a duplicate.

Mix’n’match does some automated matching based on IDs such as ORCIDs or ISNIs, and then suggests some possible matches based on names and information such as dates of birth and death.

With more than 55,000 people in the spreadsheet, there is a lot to get through. There were some 1,500 matches that were low-hanging fruit but it has taken more than two years to get nearly 7,000 matches. The approach has been to use Mix’n’match to confirm suggested matches and to manually add ADS IDs to Wikidata items; the latter is done when I’m confident I’ve found a match. The Mix’n’match suggestions were very, well, mixed so I came up with some custom searches to try to narrow things down. I looked for people who published in the field of prehistoric archaeology but who don’t have an ADS ID, antiquarians with no ADS ID, French archaeologists with no ADS ID, people who published in the Sussex Archaeological Collections with no ADS ID (and other journals with an extensive back catalogue on the ADS), and variations thereof. As it turns out, there are quite a few of each who don’t appear to be in the ADS.

Soon, there will be the decision about what to do with the remainder. Should 48,000 names be imported to Wikidata with little more than an ADS ID and we trust that they may be enriched over time? It’s a possibility, but I’ve not considered it much yet. It has the most value for Wikidata where it can be linked to another item. For now at least, the ADS have a bunch of new ORCIDs, INSIs, and Wikidata IDs they can enrich their site with, and a few entries they may want to merge.

The more information there is in Wikidata – the more sourced statements about where people went to school or university, where they worked, and so on – the more useful it becomes, and you can help add information. New to Wikidata? The University of Edinburgh have a short introductory video to get you started.