This post was written by John Byrne, Wikimedian in Residence at the Royal Society and Cancer Research UK

I’ve had two recent uploads of images released by organizations where I am Wikimedian in Residence. Neither of them are huge in quantity compared to some uploads, but I’m really pleased that an unusually large percentage of them are already used in articles. Many thanks to all the editors who put them in articles, especially Keilana for CRUK and Duncan.Hull for the Royal Society images.

The first release was by Cancer Research UK (CRUK), of 390 cancer-related diagrams, including many covering anatomy and cell biology. Many medical editors had said they were keen to have these available, and they have been quickly added to many articles, with 190 already being used, some twice, and mostly on high-traffic medical articles like breast cancer, lung cancer and cervical cancer. A BaGLAMa2 report shows page views in August, traditionally a low-traffic month, of 1.1 million

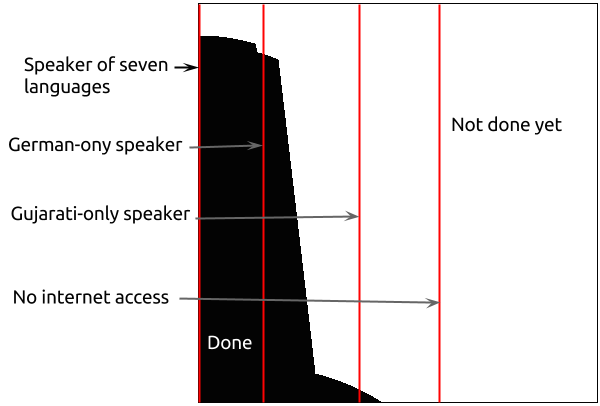

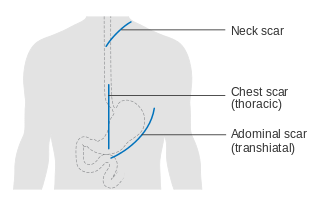

Wikipedia cancer articles tend to be mostly illustrated with alarming shots of tumours, or purple-stained pathology slides which convey little to non-professional readers. The new images are from the patient information pages on CRUK’s website and explain in simple terms basic aspects of the main cancers – where they arise, how they grow and spread. Some show surgical procedures that are hard to convey in prose.

Many files have generous labelling inside the image. All the files are in svg format, allowing for easy translation of these labels into other languages, which should be especially useful over time. All use the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International licence. All the images of this type that CRUK have are now uploaded, but additional ones should be uploaded as they are created, and other types of image, including infographics, are in the pipeline.

We are also working to change the standard model release forms CRUK uses, so that photos and videos featuring people that are made in future will be easier to release. CRUK also has some very attractive short animations, which in some ways are more culturally neutral and so preferable for use around the world. These avoid model release issues and some should be coming soon.

The other release is by the Royal Society, the UK’s National Academy for the Sciences. I’ve now completed my term as Wikipedian in Residence there, but had got their agreement to release the official portrait photos of the new Fellows elected in 2014, with the intention to continue this in future years. Some photos of their building were also released.

By early September, only a month after uploading completed, of the 72 files uploaded 38 (53%) are now used in Wikipedia articles. The portrait of Professor Martin Hairer, who won the Fields Medal this August is used in 18 different language versions of Wikipedia, having fortuitously been uploaded just before it was announced that he had won the Fields Medal, which is often called the mathematician’s equivalent of a Nobel. Most of the biographies were started after this announcement. Other images of Fellows are used in the French, Chinese and Persian Wikipedias, as well as English. There were 96,000 page views in August for these articles.

The availability of high-quality portraits is very likely to encourage the writing of articles on those Fellows who still lack Wikipedia biographies. There are 15 of these, which is already a better (lower) figures than for recent years such as 2012, where 29 still lack biographies.