By John Lubbock, Communications Coordinator

As many of you know, Wikipedia has been blocked in Turkey since 2017. While it’s still possible to access the site from Turkey via proxy sites and VPNs, it’s much harder to edit Wikipedia from Turkey, which means that the content is not being updated and the Turkish language version of Wikipedia is not growing.

I’ve been visiting Turkey regularly since 2012 to visit my partner who used to live there, and have written about the country quite often in my spare time as a freelance journalist. So I care quite a lot about access to information in Turkey, and about supporting the Turkish Wikimedia User Group there.

A couple of months ago, I asked a BBC journalist who had been a correspondent in Turkey if he would be willing to share some of the photos he had taken in Turkey on Wikimedia Commons, because some of them were quite useful images of political events, like government press conferences, political campaign rallies and the aftermath of serious terrorist incidents. Unfortunately, the BBC claimed copyright on these images and asked for them to be removed from Commons. This was because an employee’s content (produced in the course of doing their job) is the copyright of their employer, and because the BBC have an agreement with Getty Images to let them use all their staff’s photos, even those which are low resolution, taken on smartphones and posted on Twitter.

To make up for this setback, I have decided to publish my own photos from my many visits to Turkey over the years. So far I’ve uploaded over 1500 images, which is far higher than the roughly 250 images which were donated by the BBC journalist. You can see them all in the Category:Photos of Turkey by John Lubbock on Commons. Here’s just a few of them.

[slideshow_deploy id=’4756′]

Most of these photos are of Istanbul, but I’ve also visited Fethiye, Adana, Diyarbekir, Antalya, Tatvan and a few smaller towns in the East. There are some good images of the recently opened Adana Archaeological Museum, the Istanbul Archaeological Museum and the Fethiye Archaeological Museum, because, well, I like museums and one of the best things about visiting Turkey is the wide range of cultures and civilisations which have existed in Anatolia over the past few thousand years whose remains are everywhere for you to see.

In the context of the Turkish government’s blocking of Wikipedia and the ongoing European Court of Human Rights case brought by the Wikimedia Foundation to pressure Turkey to unblock the site, I think it’s important to show that the Wikimedia community can still support the Turkish Wikimedia community in various ways. That’s why I’m running a Wikipedia workshop for Turkish speakers in January to improve content on the Turkish Wikipedia about cultural subjects.

I am also working with Wikidata trainer and Histropedia creator Nav Evans to try to improve data about heritage sites in Turkey, which can hopefully be used by the Turkish User Group to run their first Wiki Loves Monuments next year. In the past, they have been unable to do this because the Turkish government’s own data about heritage sites is quite messy and hard to incorporate into Wikidata. Wikidata and Wikimedia Commons are not blocked in Turkey, so we hope that working on these project will show people in Turkey that Wikimedia projects can be important for promoting and preserving cultural heritage in Turkey which is such a large factor in their tourism industry.

Wikimedia UK would like to run more events in future for speakers of other lanaguages which can help to improve content in those languages and to meet our commitment to improving the diversity of content and contributors to Wikipedia. If you are a speaker of a language which doesn’t currently have a lot of content on Wikipedia, please consider getting in touch with Wikimedia UK and talking to us about running an event.

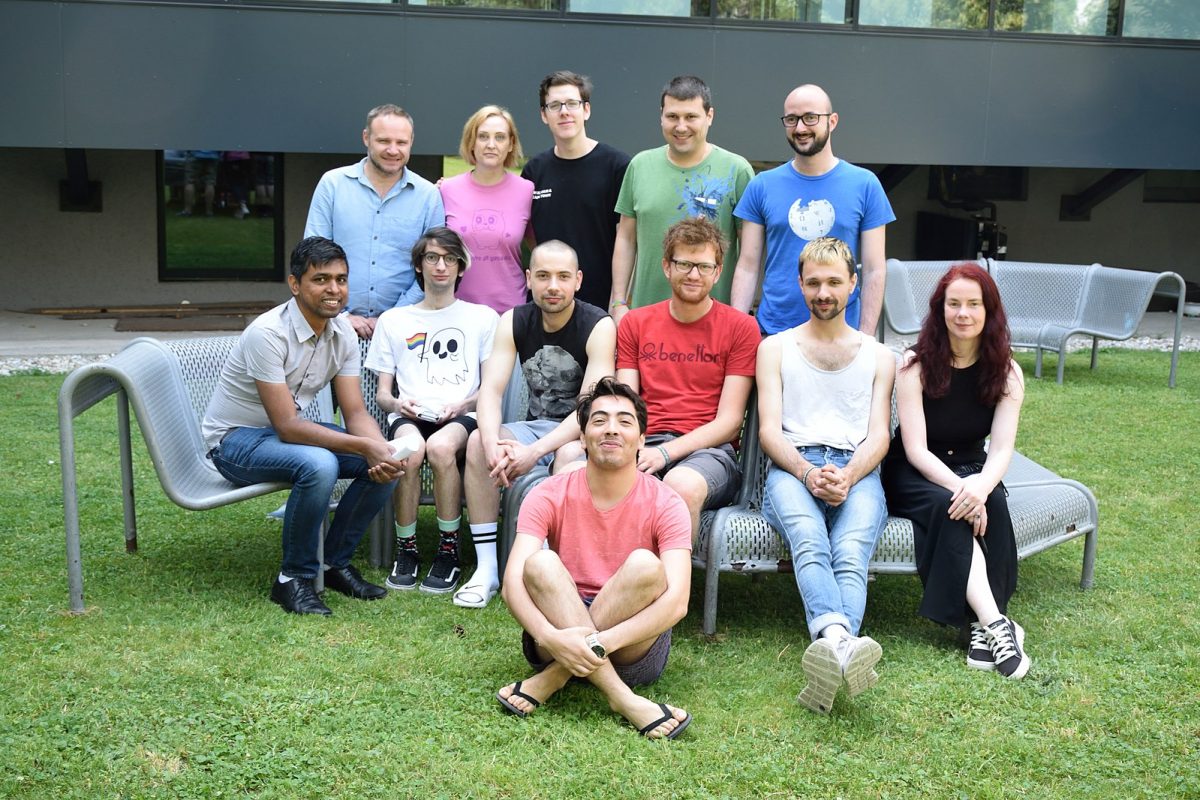

Wikimedia UK AGM 2019 –

Wikimedia UK AGM 2019 –