By Caroline Ball, Trustee of Wikimedia UK

Abstract

Wikipedia is the world’s largest information source, used daily by millions of individuals around the world – yet such is its uniqueness and dominance that rarely is the question asked: what exactly is Wikipedia? This article sets out to explore the different categories of source that Wikipedia could be defined as (primary, secondary or tertiary) alongside the varied ways in which Wikipedia is used, which defy easy categorization, exemplified by a broad-ranging literature review and focusing on the English language Wikipedia. It concludes that Wikipedia cannot easily be categorized in any information category but is defined instead by the ways it is used and interpreted by its users.

Introduction

What is Wikipedia?

At first pass, it seems like a remarkably simple question with a remarkably simple answer. The average reader knows exactly what Wikipedia is, how to access it and has probably used it on multiple occasions. Almost certainly, if asked, the average reader could explain what Wikipedia is.

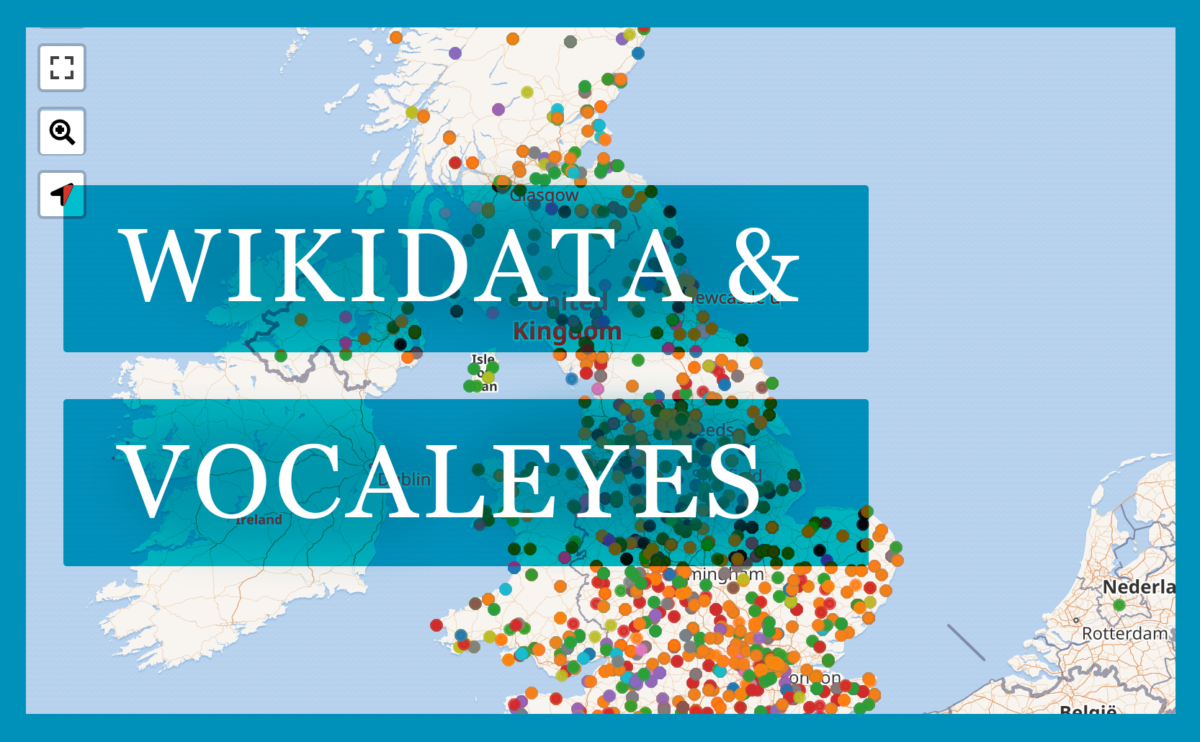

Wikipedia is a crowdsourced online encyclopaedia, indeed, the online encyclopaedia. It is one of many projects owned by the Wikimedia Foundation, a non-profit organization based in San Francisco and founded in 2003 to fund Wikipedia (itself launched in 2001) and other such wiki projects, which include media site Wikimedia Commons, dictionary and thesaurus Wiktionary, the knowledge base Wikidata and wikis for books, quotes, travels, a newspaper, tutorials and courses.1 However, Wikipedia is the oldest, largest, and almost certainly best known, of all the Wikimedia projects.

In terms of coverage, usage, currency and public awareness, its nearest online rival, Encyclopaedia Britannica, does not even come close. Encyclopaedia Britannica contains an estimated 120,000 articles;2 as of writing, the English language Wikipedia contains 6,552,009 and rises by roughly 17,000 articles a month.3 How the two compare in terms of perception, accuracy, bias and reliability is another issue entirely, one that has been amply addressed elsewhere.4

Much research has also been done on Wikipedia and its sister projects, and how it is used for, by and within education and research communities and the wider public – as an information source,5 a teaching and learning tool,6 a source of Big Data,7 an example of crowdsourcing,8 as a collaborative dissemination tool for museums and archives9 and many other uses.

However, little of this research has taken its analysis of Wikipedia one step further to reflect on how that varied use might provide insight into Wikipedia’s own ambiguous position as an information source; it generally proceeds from the assumption that there is a clear-cut definition of what exactly Wikipedia is.

For example, the focus on how dependable, accurate or biased Wikipedia is in comparison to other information sources rests on the assumption that Wikipedia can be compared to other equivalent information sources. Part of what this literature review intends to highlight is that there is no resource equivalent to Wikipedia, that it stands apart as a unique experiment in crowdsourced information production, synthesis and retrieval (what Mehdi et al. describe as a ‘multi-purpose knowledge base’,10 and that it straddles the traditional categories of primary, secondary and tertiary sources, requiring what Magnus describes as ‘new epistemic methods and strategies’11.

Taking an in-depth look at each of these categories, this review will draw on published research to assess how Wikipedia’s content, and the various uses to which different users can put it, conforms to each category and what the implications are for our understanding of Wikipedia.

To begin with, we must break Wikipedia down into its many component parts to adequately discern the whole: what we term ‘Wikipedia’ comprises more than just the most obvious and visible element, the articles. There is the site itself, Wikipedia, as a collective term comprising the entire contents, from articles to talk pages, policies, guidelines, statistics, documentation and user pages. There are the individual articles, what we usually think of as defining ‘Wikipedia’. There are the references and onward links, directing users to further reading and citational evidence. There is the data that Wikipedia generates – statistics on almost every element of creation and use. There are Wikipedia’s own policies, guidelines and templates. All of these elements are ‘Wikipedia’, and all are used in various different ways, depending on the user and the need.

Methodology

This literature review is not intended to be systematic and relies on mapping the themes of the intended research against the corpus of literature available, as opposed to identifying and evidencing all relevant existing research. The intention is to be illustrative of the varied research on Wikipedia usage, rather than to provide an exhaustive exploration of it. This review was not, therefore, conducted according to the relevant principles of systematic reviews. However, a rigorous search methodology and strategy was employed.

A wide range of multi-disciplinary databases were searched, both full-text and index, for articles detailing research based on, referring to or utilizing data and information from Wikipedia (including but not exclusive to EBSCO databases, Emerald, SpringerLink, ScienceDirect, Ovid, Wiley, Taylor & Francis, CINAHL Ultimate, IEEE and Scopus).

To ensure the relevance and sensitivity of the search, search terms were limited to the title and the abstract of records, where the database allowed the option to search these fields. Results were excluded if Wikipedia was not the primary focus of the article, if the article was not available in English or did not refer to the English-language Wikipedia.

Serendipitous discoveries of relevant research were also made via the WikiResearch Twitter account @WikiResearch, the ‘Wiki-research-l’ mailing list and the Wikimedia Research biannual reports.

Wikipedia as tertiary source

We shall begin with the most obvious categorization of Wikipedia – as a tertiary source. This is how encyclopaedias have traditionally been defined throughout the ages and indeed how Wikipedia defines itself: ‘Wikipedia is a tertiary source: Wikipedia summarizes descriptions, interpretations and analyses that are found in secondary sources, or bases such summaries on tertiary sources’,12 although in quoting Wikipedia’s own definition of itself in this manner I am in fact using Wikipedia as a primary source, thereby undercutting that initial apparently clear-cut definition almost immediately!

Many articles describe Wikipedia as a tertiary source without comment.13 However, there is no standard dictionary definition of what a tertiary source is, how it functions or is used. Wikipedia’s definition is one, but this research has provided others: ‘when literature is primarily used as a source to locate primary and secondary sources, and does not provide any new information, then it is called as tertiary source’;14 ‘the primary function of tertiary source is to aid the searcher of information in the use of primary and secondary sources of information’;15 ‘the synthesizing of primary and secondary sources’.16

There can be little doubt that Wikipedia articles synthesize or summarize primary and secondary sources, and that, theoretically at least, these articles serve as a means of locating those sources.

One of the three core content policies of Wikipedia is verifiability, alongside that need for a neutral point of view and the ban on original research, i.e. research that has not been published elsewhere17 – except when it comes to research about itself – undercutting that easy definition again. Wikipedia articles must reference published secondary or primary sources to verify facts or claims within articles – statements missing this means of verification are flagged with a ‘citation needed’ tag and the article itself may contain a ‘needs additional citations for verification’ template at its head, as a means of warning users of the potentially misleading or inaccurate (or at the least, unverifiable) statements contained within a given article.

One of Wikipedia’s key elements, and one that has itself given rise to a great deal of research, is the issue of notability – a subject must be considered notable enough to be covered by sufficient secondary sources.18 An article without sources will be flagged for speedy deletion. However, who or what is considered notable is often the subject of a great deal of debate and varying perspective, and the ‘notability’ policy is often used to the detriment of female subjects and topics.19 It does however highlight the significant importance Wikipedia places on independent verifiable sources for its content.

An essential element of a tertiary source is that it is considered a means to further information, not an end, as per the previous definitions by Wikipedia, Durai and others. Wikipedia has been described as a ‘bridge’ to further information,20 a ‘gateway’ through which the world seeks knowledge,21 a ‘means, not an end’.22 One would expect therefore to see Wikipedia users’ behaviour reflect this.

Whilst this is a neglected area of research, and one rich with possibility for future investigation, a recent study logged all access clicks for links for external references within Wikipedia during a one-month period and found ‘overall engagement with citations is low: about one in 300 pageviews results in a reference click (0.29% overall; 0.56% on desktop; 0.13% on mobile)’.23

Follow-up research estimated that Wikipedia generated 43 million clicks a month to external websites,24 i.e. users following article citations to their source. However, that initially impressive-looking statistic needs to be balanced against Wikipedia’s estimated average monthly pageviews of roughly 7 billion,25 demonstrating that again less than 1% of users follow citations to their source.

This research demonstrates that most users (over 99%) do not use Wikipedia as a ‘bridge’, ‘a gateway’ or as a means to discovering primary and secondary sources, thereby undermining those apparently clear-cut assumptions about Wikipedia as a tertiary source, as defined by Grathwohl, Cronon, Durai and Malipatil and Shinde above.

Wikipedia as secondary source

Wikipedia defines a secondary source as a ‘document or recording that relates or discusses information originally presented elsewhere,’ containing ‘analysis, evaluation, interpretation, or synthesis of the facts, evidence, concepts, and ideas taken from primary sources’.26

This would appear to be the most obvious of categories into which to fit Wikipedia. There is no question that most of the material contained within Wikipedia articles comes from elsewhere, serving as a summary of the published material on a particular topic. This is an essential element of Wikipedia’s ‘no original research’ policy: Wikipedia articles must report and summarize verifiable facts, backed up by published material, largely in pursuit of another of Wikipedia’s core policies, that of the ‘neutral point of view’. Including analysis, evaluation or interpretation in articles necessarily opens the door to bias and perspective (although research has shown that this is still not entirely successful, and that Wikipedia tends to lean leftwards).27

However, intent is one thing; the reality of its use is something else. Evidence explored below suggests that Wikipedia is still frequently cited as a source, both within the academic community and outside of it, despite comments such as Bould et al.’s that ‘citing Wikipedia or any other tertiary source in the academic literature opposes literary practice’.28

This indicates blurred lines between the widely accepted perception of Wikipedia as a tertiary resource and the way in which it is used alongside secondary sources such as textbooks and journal articles. Indeed, a study by Meers, Gibbons and Laws29 identified a complex interaction between what they refer to as ‘official’ (journals, textbooks etc.) and ‘unofficial’ knowledge (Wikipedia, websites etc.), with students switching frequently between the two and using the information from one to inform their understanding of the other.

Many studies have focused on student use of Wikipedia as an information source,30 with upwards of 87% reporting using it.31 One study even demonstrated that Wikipedia was the most used resource – and the library the least – among medical students.32 It has also been used as a means of educating students on issues of systemic bias in information sources.33

Of course, it is not just students using Wikipedia. Estimating the scale of citations of Wikipedia itself as a source across published research is almost impossible, largely because there is no mechanism for assessing metrics for a crowdsourced resource with no named author, or indeed even an accepted naming convention. (Searching for ‘authors’ within references on articles about Wikipedia within a bibliographic database such as Scopus highlights this issue – ‘Wikipedia’, ‘Contributors, W.’, ‘Wikipedia contributors’, ‘contributors, W.’, ‘Anonymous’, ‘Wikipedia, C.’, ‘Wikipedia.org’ and others are all used to a greater or lesser extent.) However, given the volume of research focusing on Wikipedia’s use within specific contexts, it is clearly widespread and growing.34

Several studies have concentrated on citations to Wikipedia within scholarly publishing,35 with a study by Bould et al.36 particularly demonstrating that citations to Wikipedia were not restricted to low or no impact factor journals but could be found in journals with high impact factors. A study by Tomaszewski and McDonald37 found that the highest usage was within the sciences and the lowest within arts and humanities.

Wikipedia use is not just restricted to the academic world. In the legal field, for example, several articles have discussed the practice of Wikipedia being cited as a source within judicial opinions38 – sometimes as a source of information on legal procedure and precedent, or more frequently as a source of facts. However, this latter practice resulted in at least one case being dismissed as a result.39 Use of Wikipedia in this context is rarely presented as a positive,40 but the practice clearly was and continues to be widespread enough to be the subject of academic research. Intriguingly, one of the articles cited above even specifically describes Wikipedia as a secondary source.41

There is also research equating Wikipedia with traditional secondary sources of information such as textbooks, either implicitly or explicitly. For example, numerous articles have focused on comparing the accuracy of information within Wikipedia on a particular topic with similar information contained within textbooks – in pharmacology,42 history,43 medicine,44 sociology45 – a comparison that only makes sense if the two resources are considered to be comparable.

An intriguing study by Rahdari et al.46 even focused on how concepts of smart learning could be used to provide recommendations for external supporting material, namely Wikipedia articles, when students were finding e-textbook material challenging to understand, again equating the two.

Wikipedia as primary source

One topic in which there can be no question that Wikipedia serves as a primary source is that of Wikipedia itself.

As can be seen from this review alone, there is no way of writing about Wikipedia without referring frequently to the content it puts out about itself – from its own policies and guidelines to the statistics about the site, articles and its usage. There can be no denying that whilst ‘citing Wikipedia or any other tertiary source in the academic literature opposes literary practice’, as Bould et al. have argued, ‘Wikipedia may be the most appropriate source to cite … in situations in which Wikipedia is used as part of the scientific methods’.47 Note the implicit acceptance of the definition of Wikipedia as solely a tertiary source.

For example, a search within the bibliographic database Scopus for references of the page ‘Wikipedia: Statistics’,48 which contains data and statistics for various elements of Wikipedia, including edits, views, size, growth, editors, demographics, etc., returned 155 individual journal articles. A similar search on Wikipedia’s page on its notability guidelines49 returns 33 journal articles. With these instances as examples, it is noticeably clear that Wikipedia is being used and referenced as a primary source, at least when it comes to content that relates to itself. (As a further example, Wikipedia as a source has been cited eight times in this literature review.)

Part of the core tenet of Wikipedia is transparency. Because everything about Wikipedia is openly available, from its guidance and policies to its inner workings and data, it can serve as an immensely useful source of data for vast swathes of research.

Wikipedia editing and pageview activities have been used as a tool to predict everything from movie box-office success50 to electoral results51 and stock market movement.52 Studies have investigated how Wikipedia pageviews can correlate with official tourism indicators,53 how copyright restrictions affect citations and knowledge reuse54 or to determine whether the ‘Ice Bucket Challenge’ increased people’s awareness of ALS.55

One area in which Wikipedia data (most particularly statistics allowing for the tracking, quantification and geolocating of pageviews) has been heavily drawn upon is in the field of health research. Wikipedia is the most used resource globally for medical information,56 by both members of the public57 and healthcare professionals,58 and as such can provide an enormous source of information on both individual and group information-seeking behaviour and the implications and motivations of that behaviour.59

For example, research has focused on the use of trends in, and analysis of, Wikipedia searches and pageviews as an indicator of global disease outbreaks,60 from measles,61 influenza62 and swine flu63 – to even predicting deaths from coronavirus.64

Further evidence could be drawn from almost any field of study – in sociology, for example, exploring the democratic creation of knowledge and the concurrent promises and pitfalls65 or the under-representation of women.66

In the field of conservation, Wikipedia pageviews have been used for exploring the cultural importance of global reptiles,67 to evaluate public interest in protected areas68 and online sentiment towards iconic species.69

Data harvested from Wikipedia has informed demographic studies on social media use and topic diversity,70 in disambiguating and specifying social actors in big data by using Wikipedia as a data source for demographic information,71 even in assessing the life expectancy of professional occupations via the mean age of death data available via Wikipedia biographies!72

Focusing on citations in the reverse direction, some research has focused on academic citations within Wikipedia articles as a means of evidencing the reach and dissemination of research within the wider general public, alongside more traditional academic citation-focused measurements.73

Several studies have compared references to research from Wikipedia alongside Facebook, Twitter and other social media resources and found strong correlation between these altmetrics and the UK Research Excellence Framework (REF) reviewers’ scores, indicating that altmetrics from sources such as Wikipedia could be used as a formal means of assessing the impact of scholarly research.74

Conclusion

Drawing on published research demonstrating the variety of ways in which Wikipedia has been, and continues to be, used (many of which defy the initial simple categorization of Wikipedia as a tertiary source), this review has hopefully demonstrated how the everyday usage of Wikipedia by millions of individuals globally differs markedly from the stated intentions and function of the encyclopaedia itself.

The concept of variation theory is frequently used to explain how different learners, participating in the same learning experience and with access to the same learning materials, can come to understand a concept differently.75 In this context, it can be used to demonstrate how an object of learning (i.e. Wikipedia) ‘changes shape during its way from the intended (planned), enacted (offered) and lived (discerned) object of learning’.76

As can be seen from the research drawn on within this literature review, many of the uses Wikipedia can be put to could almost certainly not have been foreseen by founders Jimmy Wales and Larry Sanger when they set out to ‘pretty single-mindedly [aim] at creating an encyclopaedia’,77 since these uses have resulted from the way it has been structured (enacted) and the lived experience of those using it. This review can begin to serve as an explanation of how individuals’ understanding of Wikipedia’s categorization as an information source can, according to variation theory, similarly differ based on a range of distinct factors, but in this context, most particularly how they use Wikipedia. Leaving the world of literature review and theory behind and moving into practice, further research would seem to be required on how an individual’s use of Wikipedia is shaped by their own understanding of what kind of source it is and how it should be used, both for education, research and general knowledge seeking.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

A list of the abbreviations and acronyms used in this and other Insights articles can be accessed here – click on the URL below and then select the ‘full list of industry A&As’ link: http://www.uksg.org/publications#aa.

Competing interests

The author is a trustee of Wikimedia UK, which is an unpaid voluntary position.